Narrative Watch with Big Local

A collaboration with Big Local News focusing on accessing and archiving police body cam footage

On December 12, 2023 The Grio published two articles about police body cam footage, in partnership with Big Local News and The Starling Lab for Data Integrity. Both articles address the difficulty in using and obtaining body cam footage from police departments, despite regulations put in place aimed at facilitating police accountability.

This collaboration surfaced records related to the beating of Tyre Nichols in Memphis, Tennessee, and were a part of the research completed by Big Local News. These records were sourced from the City of Memphis website, and videos were sourced from the City of Memphis Vimeo account. They were archived and preserved by the Starling Lab for Data Integrity using authentication technologies for video and web archiving.

These tools underscore the importance of accuracy, preserve immutable records of evidence at risk of disappearing or being unavailable through other means, and serve to combat mis- and disinformation.

By using emerging cryptographic methodologies and decentralized systems, these public records can now be protected from disappearance and made available for the public to review, should the source or authenticity of the digital media be called into question. This problem is becoming more acute with the rise of Generative Artificial Intelligence. For example, should the video released by the City of Memphis be manipulated in the future, we now have that original video authenticated and stored.

Decentralized tools can create an audit trail (or “chain of custody”) that identifies the history (known as provenance) of a piece of digital content. This serves to reduce information uncertainty and bolster trust in digital records. In the process of creating audit trails, Starling Lab surfaces metadata, which is data about digital media.

When Starling archived these public records, an immutable digital ‘fingerprint’ called a hash was created using a mathematical formula to establish a snapshot of the records captured. If any single byte of the data is changed, be it a pixel of an image or the timestamp of when it was collected, one can use the hash to verify if a copy is different or manipulated. A hash mismatch is an indicator of altered data. It functions like a tamper-evident seal.

A hash is nearly impossible to fake, and the hashed data can also be signed with a cryptographic signature. This cryptographic tool makes it so we can attest to exactly what was created and when. Signing with a cryptographic key (pair) makes it possible to sign these records with a known identity, and give your ‘stamp of approval’ to a set of metadata and media. Hashes are also used to create the CIDs (Content IDentifiers) that we use to name the files with original videos, websites, and metadata related to the media.

A hash protects an original version of the public record that can be used down the line if the source of this research, the videos and archives of webpages, is called into question. It also helps protect important records like these from disappearing.

These records, or the hashes of the content, were also registered on various blockchains to establish exactly what content existed, and when it existed.

Archives

These records are stored in a distributed, peer-to-peer data sharing system called IPFS (InterPlanetary File System) from which users can download and view copies of the archives.

These same files are preserved on a distributed archival storage network called Filecoin in a long-term agreement with Filecoin providers that store this data. Users can inspect these deals and the identity of the nodes who are archiving this data.

Last, metadata records for each of the files were registered on the blockchain, so users can validate what content existed, and when we established the record of their existence.

For example, this registration on the Numbers blockchain of one of the videos posted of Memphis PD body cams contains a pointer to the metadata file on IPFS labeled as “assetTreeCid”. In the metadata file you will find both a CID for the original content, as well as a Content ID for the entire archive.

Users can validate these records against the version of the videos they have to see if that version has been altered, faked, or modified.

IPFS File Copies

Original Body Cam Videos – Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4

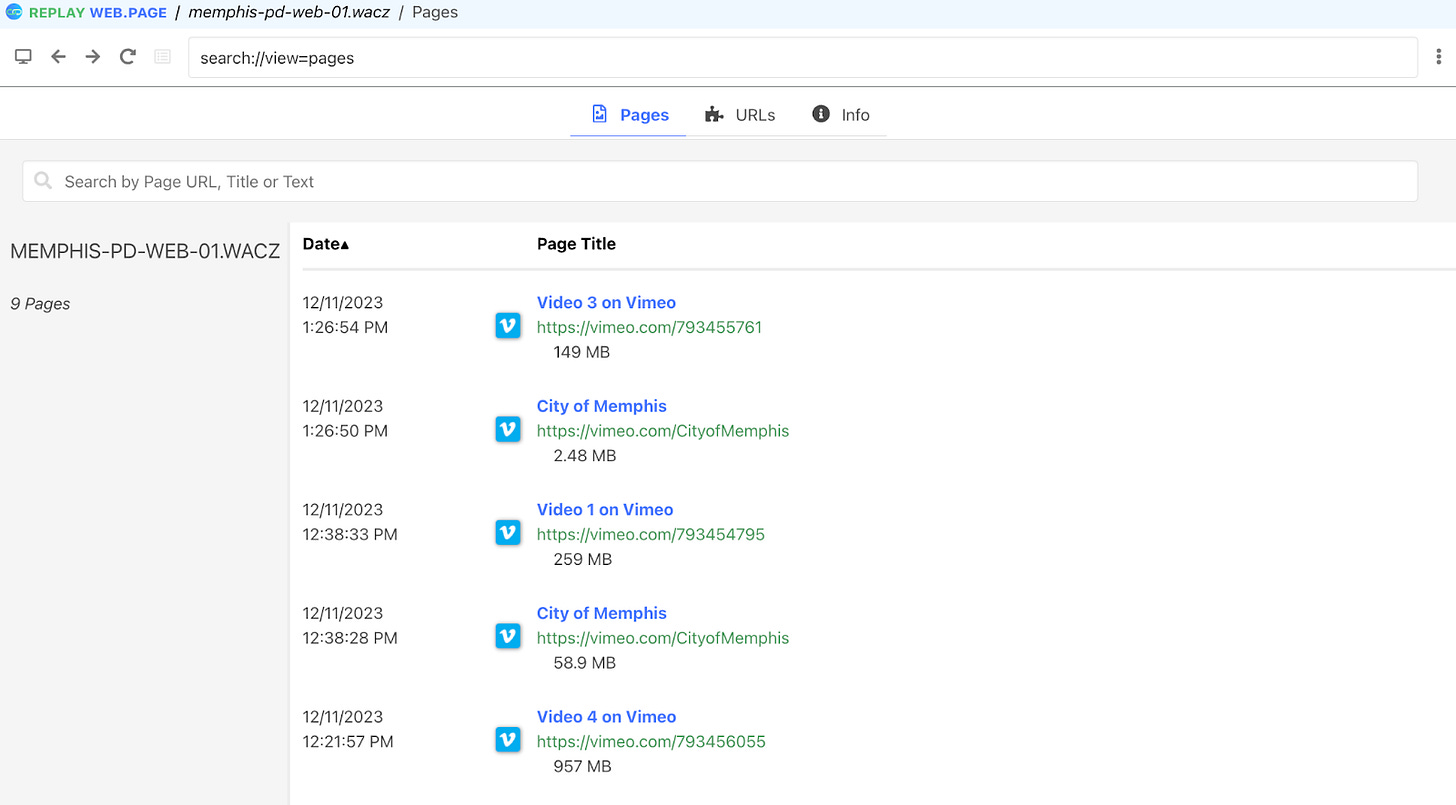

Website Archives – Vimeo Webpages | Memphis PD Website

Filecoin Archive Information:

Records of Storage – Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4 | Vimeo Webpages | Memphis PD Website

Blockchain Registrations:

Numbers – Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4 | Vimeo Webpages | Memphis PD Website

Avalanche – Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4 | Vimeo Webpages | Memphis PD Website

ISCN on Likecoin– Video 1 | Video 2 | Video 3 | Video 4 | Vimeo Webpages | Memphis PD Website

How to Download and Inspect Records

Click on the IPFS Registration link to download this from the distributed storage network

Locate where you downloaded the file. It should be in your Downloads folder and have a name that looks like babyf6g3sdb…

For videos, change the name by adding a .mp4 the end of the filename for body cam videos, and for the web archives add a .wacz to the end of the filename

You can open the .mp4 file on your computer

You can open the web archive files by visiting the website https://replayweb.page/ and dragging and dropping the .wacz files into the web interface.

Validate the videos and web pages you have a copy of are the same ones registered on the blockchains by looking at the metadata record called

"assetTreeCid". You can view this record by using an IPFS gateway with one of theassetTreeCids from a blockchain registration record, such as https://ipfs-pin.numbersprotocol.io/ipfs/<assetTreeCid>.Example: https://ipfs-pin.numbersprotocol.io/ipfs/bafkreiauefa46ksrrtvws7g6wszvck7jaf5oorwb3wf7dv7dykyljo3kq4