Pilot Project on Making Web Preservation Accessible for Investigative Journalism

Tracking the illicit flow of cars from Europe to Russia, reporters found their sanctions-evasion scheme was a red herring: a sophisticated scam targeting Russians, complete with deepfaked videos.

In the digital age, the “smoking gun” is often a fleeting URL, a social message that gets edited minutes later, or a listing on a grey-market website that vanishes once a sale is made.

Today, we are proud to announce the publication of “Sanctions, Scams, and Deepfakes,” a major investigation by our partners at Airwars into the illicit flow of luxury cars from Europe to Russia. Starling Lab worked in support of the investigative team to preserve the digital evidence supporting their findings, while the reporters traced the physical movement of vehicles across borders.

At least, that’s what they originally set out to do.

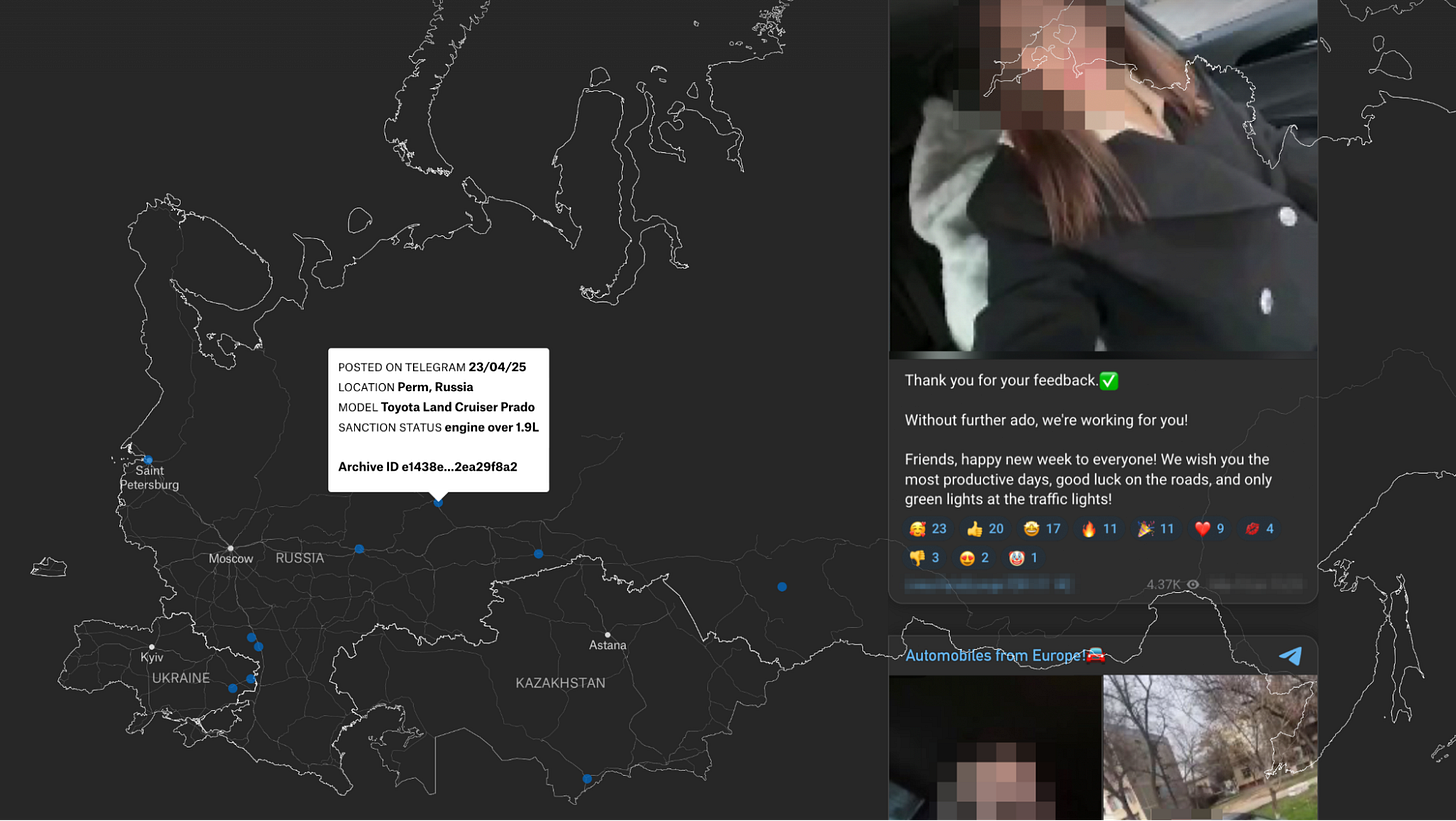

At the center of this investigation into the apparent smuggling operation of cars into Russia laid a red herring. The investigative team initially believed they were tracking real sanctions-evasion schemes bringing luxury cars from Germany to Russia, but instead discovered the operation was largely a scam targeting Russians themselves. The deepfaked video of a legitimate Russian car dealer explaining the smuggling process, the paid actors posing as satisfied customers, and the geolocated cars in Germany were all elaborate deceptions designed to make the fraud appear credible – with potential victims losing thousands of euros to scammers likely operating from Ukraine rather than to actual smugglers delivering sanctioned vehicles.

The investigation was supported by IJ4EU, a grant scheme for cross-border investigative journalism in Europe. The Starling Lab did not participate in the grant application, nor did it receive any funds. Our support of the investigation was purely pro bono and limited to that project.

Technical Stack Deployed

During the investigative phase, the research and investigative team needed to browse hundreds of online sources, from Belarusian border cam footage to social media and social messages.

The core technical challenge was clear: How do we allow investigators to move fast while maintaining a forensic chain of custody? A simple screenshot is insufficient for legal or historical proof. We needed a system where an investigator could claim, “at this time and date, I browsed this unique URL which contained precisely this content,“ and be able to back it up with cryptographic proof.

Fortunately, we have been working with state-of-the-art web archiving tools for years – and have even produced a whitepaper on best practices for web archiving. The approach described in this project aims to ensure the collected material meets the high bar for authenticity and probative value required in legal proceedings. It directly addresses the belief that these tools and techniques can be cumbersome or slow down the investigative process.

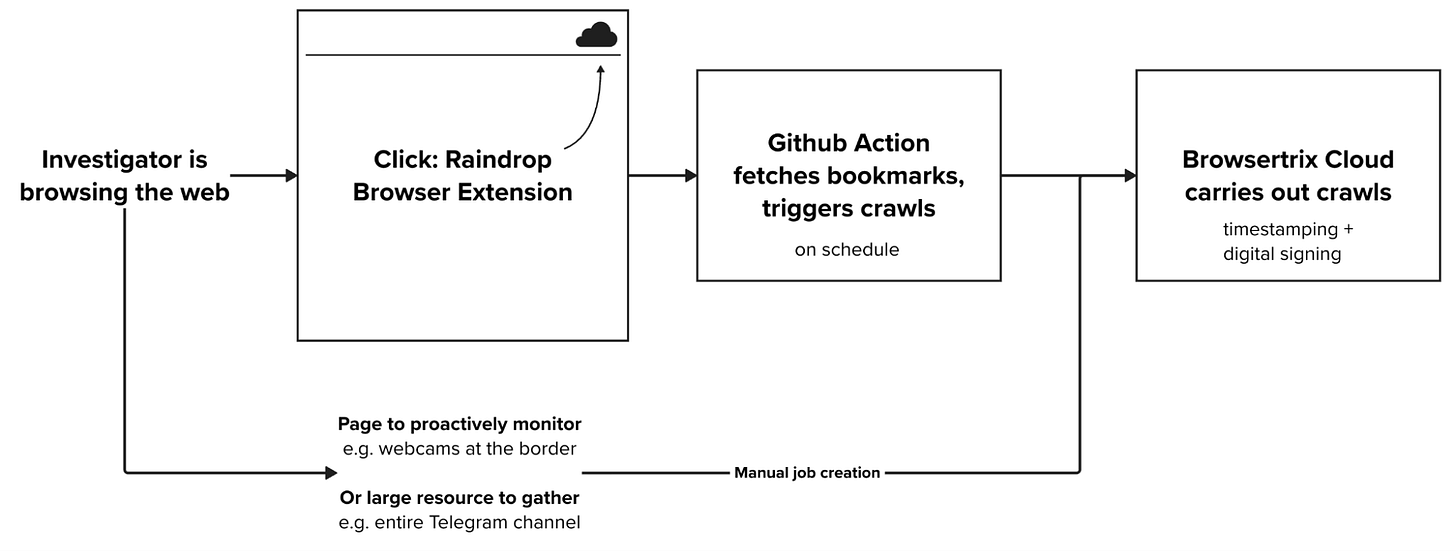

This perception being a key barrier to adoption, we set out to build a bridge between consumer-friendly tools and forensic-grade archiving. We recommended the team use Raindrop.io, a lightweight browser extension, to bookmark relevant links and add annotations. This allowed the investigators to simply “click and save” without leaving their browser.

Behind the scenes, however, a preservation pipeline was built: on schedule, Github Actions would trigger Typescript scripts tasked with fetching new bookmarks that might have been added to Raindrop; and where appropriate, to schedule their individual crawling in the Starling Lab Browsertrix Cloud account.

In total, we preserved more than 9,000 unique URLs, totalling 98 GiB in compressed form.

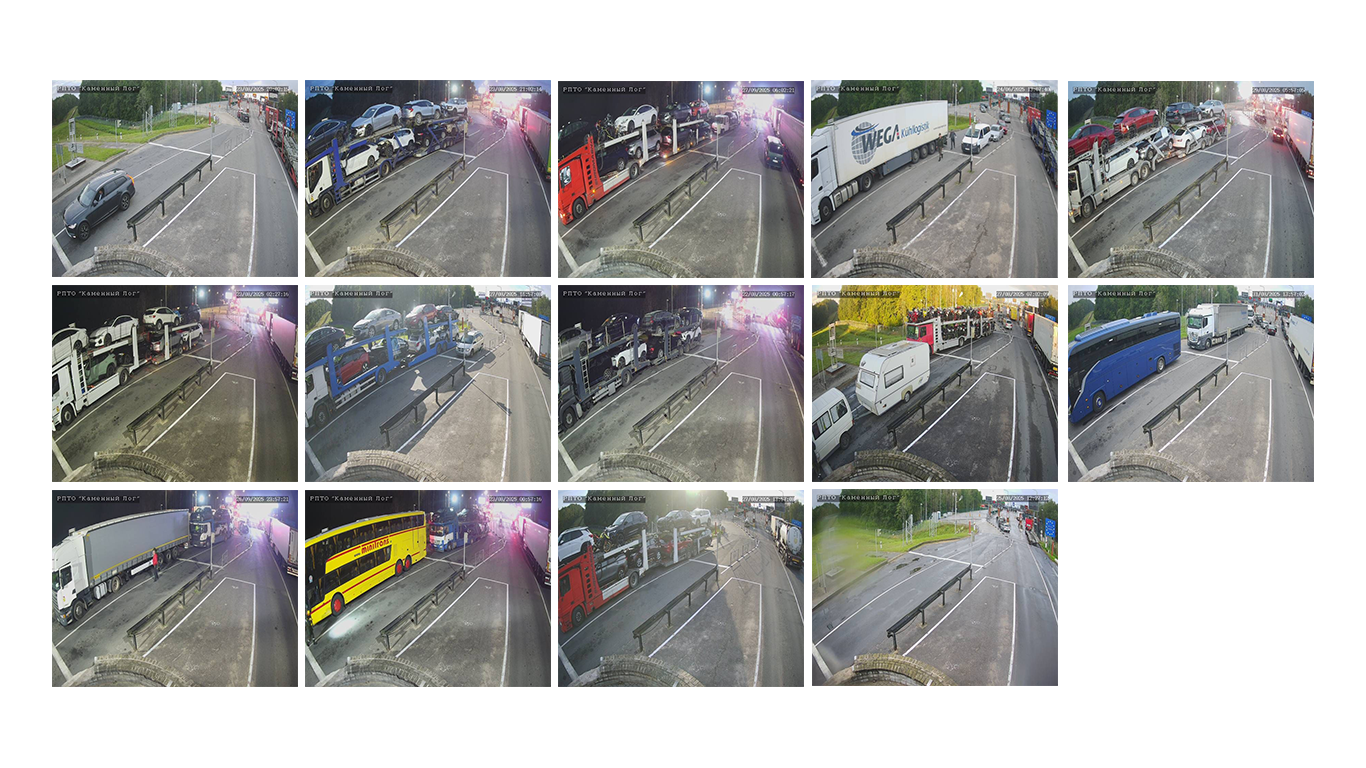

A major early lead was the case of the border crossing between Lithuania and Belarus, which the team understood as a key milestone in the supply of cars into Russia. The border crossing is monitored by webcams that refresh every 10 minutes or so. By running our crawls on schedule, we were able to provide the team once a day with a collage of captures – in the hope of substantiating that one of the known delivery lorries was doing the journey, as the Telegram channel seemed to claim e.g. below:

Despite monitoring the webcams for a month and a half, reviewing about 3,800 photographs (two shots every 10 minutes most hours of the daytime), we were not able to find one of the known trucks.

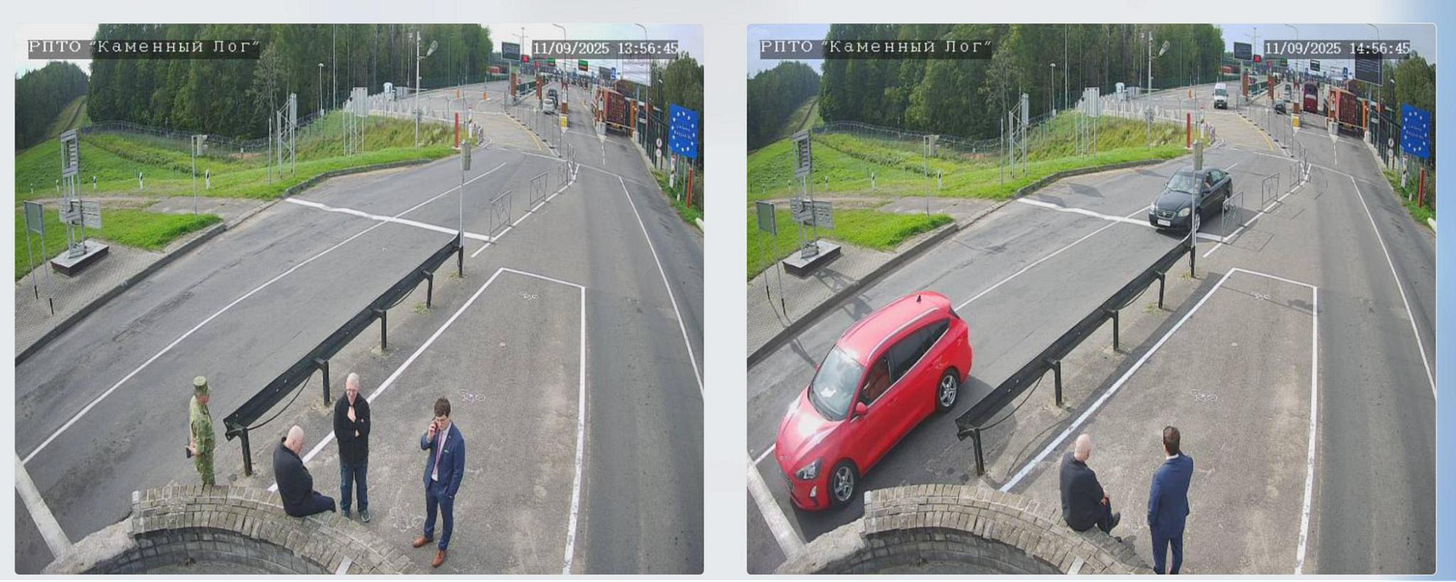

We, however, witnessed the spectacle of political opposition Mikalai Statkevich sitting in this no-man’s land after having been freed from Belarus, reportedly refusing to walk to Lithuania and go into exile.

Learnings

Proactive engagement

The earlier and the more closely we are involved, the better our chances to do good work. This oft-repeated canon of collaboration is worth its salt for a reason.

In the context of this investigation, we think we were able to support the collection of web content to a fair extent. Frequent touchpoints with a team helped identify developing parts of their workflow - for example the need to monitor the webcam photographs, which were being overwritten relatively frequently.

Time and opportunity to engage

As the story pivoted from tracking the supply chain to the realisation that key elements had been fabricated and were deepfakes or shallowfakes, the pressure to make a looming deadline led to a tightening of the loop on the investigative team’s side. The result of that was material received by investigators in the last days, prior to publication, was not shared with us for authentication and preservation.

Furthermore, we had prepared for a planned field trip to dealerships in Lithuania, and ran a short training for reporters on using the Proofmode app to take photographs, cryptographically seal them, and share them on – this trip however never materialized as the story pivoted away.

Seeing as the investigation relates to both forgeries and inauthentic material, we regard these omissions as missed opportunities.

The need for redactions

The pre-publication legal review sought by Airwars led to a cautious treatment of the evidence collected. The story was complex, with a good deal of uncertainty about what was real, and which of the persons and organisations involved were in full possession of the facts.

While technically well within reach, we opted to not publish full embeds of the Telegram posts and messages, as well as to redact some metadata from them. We are also not making the archive publicly accessible. These measures aim to protect car sellers, dealerships, clients, and anyone else whose photographs might have been used against their will and in support of the scam.

This case study further underscores the need for verifiable redaction technology to be part of the feature set of web archiving tools for journalists. In service of this requirement, we have deployed techniques from the field of Zero-Knowledge Proofs in our Rolling Stone investigation into war crimes in Bosnia. This technology allows publishers to redact sensitive information (such as names in documents or metadata in digital files) while generating a mathematical proof that certifies only specific pixels or data fields were obscured.

Scaleable

This pilot project allowed us to test and refine a preservation mechanism that is both robust and non-intrusive to the investigative workflow. We are eager to further deploy the processes developed during this collaboration, and this model more broadly, for future investigations and other partnerships with journalistic organizations.